Explosion of Deadly Ticks Fueled by Climate Change, Ravaging Moose, Infecting People and Pets

(EnviroNews DC News Bureau) — EnviroNews Exclusive: Warmer, shorter winters due to climate change are a boon for the ticks that harm people, their pets and wildlife, scientists told EnviroNews in a series of exclusive interviews for this report.

A walk in the woods can be refreshing, fun and good exercise. New England poet Robert Frost described his strolls as “lovely, dark and deep.” Henry David Thoreau encouraged his readers to get back to the wilderness, while many of Beethoven’s greatest pieces were inspired by nature’s splendor. But those great men all lived in simpler times.

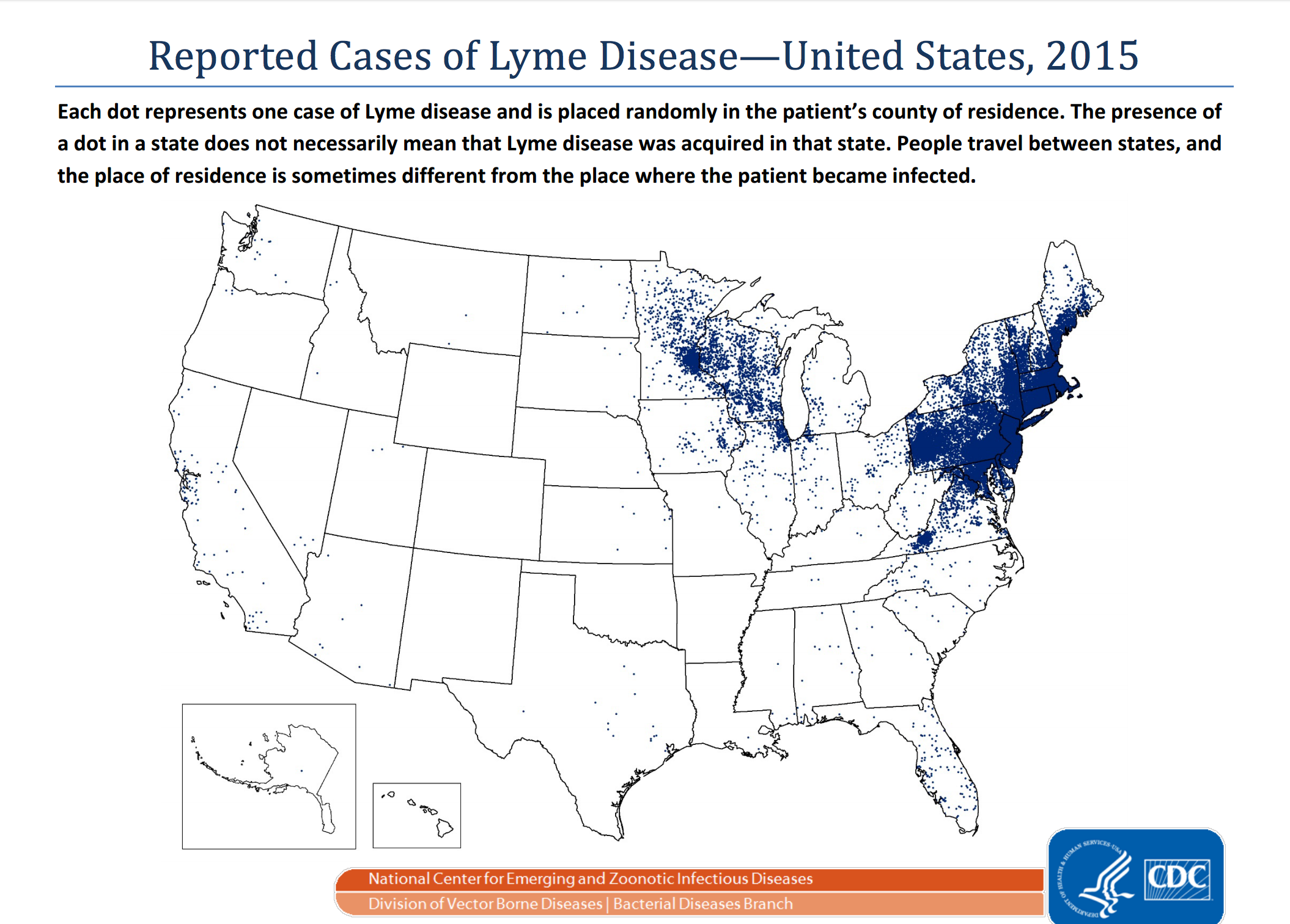

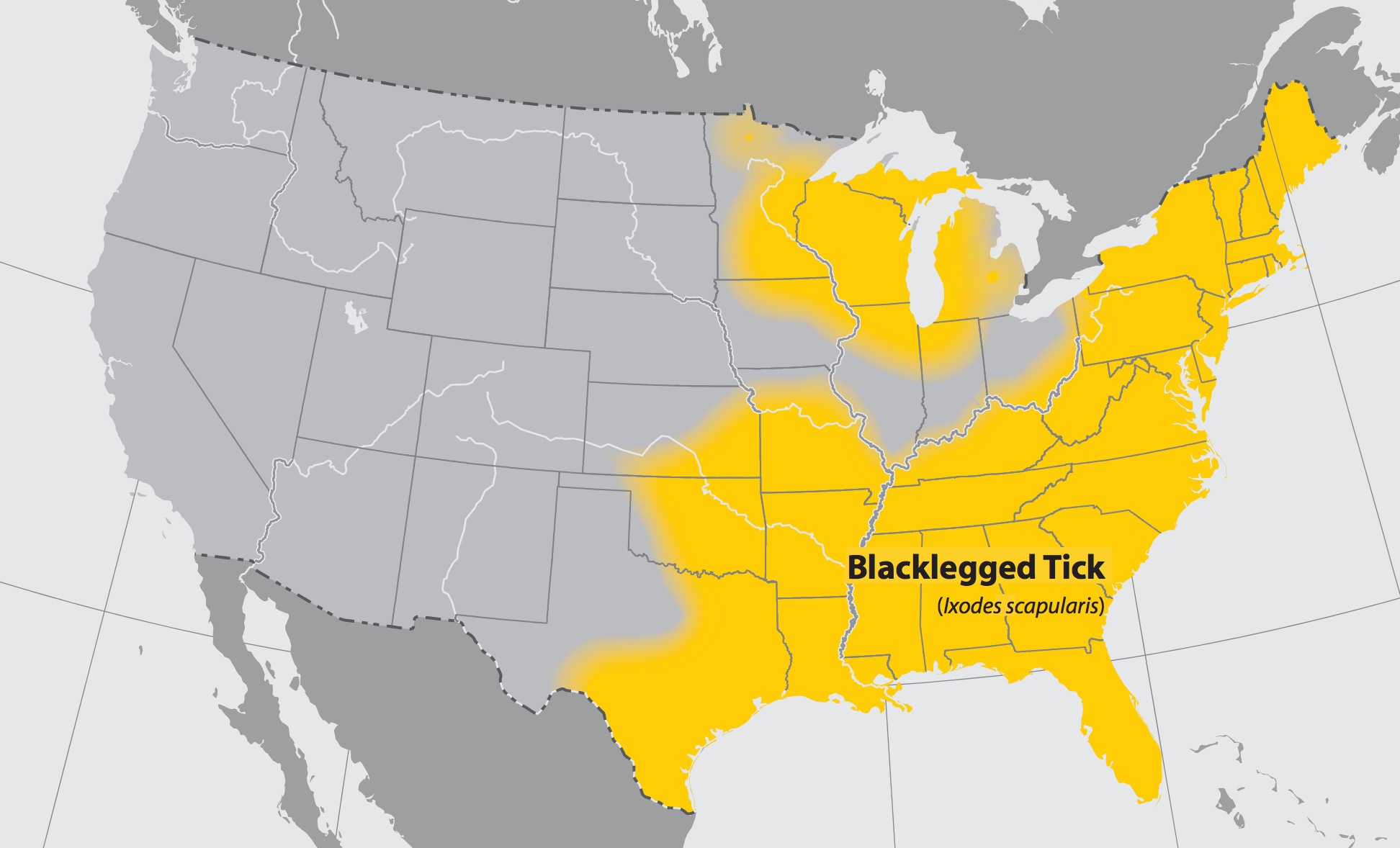

Lyme disease, spread by ticks, is now the fastest-growing vector-borne infectious disease in the U.S. Deer ticks (Ixodes scapularis) and western blacklegged ticks (Ixodes pacificus), both of which can carry Lyme, are now found in 41 states and one-third of all U.S. counties.

Maine saw a record number of Lyme cases in 2016. Ohio’s Erie County reported a record 186 Lyme cases in the same year and nearby Cuyahoga County, which formerly averaged 26 cases every five years, saw 44 last year alone, according to Cleveland’s WEWS News 5. Deer ticks are common in Wisconsin and Minnesota, while populous Mid-Atlantic states including Pennsylvania and Virginia are rife with the disease-carrying arachnids as well. Even Martha’s Vineyard is a known hotspot for Lyme-carrying ticks.

A 2011-2012 survey found that nine percent of Appalachian Trail (AT) hikers said they had been diagnosed with Lyme disease. That means you have nearly a 1-in-10 chance of contracting Lyme if you hike the AT. And this year may pose an unusually high risk according to Richard Ostfeld, a disease ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies.

Although Lyme disease has been around for thousands of years, it wasn’t recognized in the U.S. until the 1960s and 1970s. That’s when a cluster of patients in Lyme, Connecticut were found suffering from an undiagnosed illness that left them with skin rashes, headaches, chronic fatigue and other symptoms. By 1982, scientists had identified the bacteria responsible for the disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, and linked it to ticks.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), ticks will bite any part of the human body, but in most cases need to be attached for 36 to 48 hours before the Lyme spirochete can be transmitted. The first signs of infection, which can occur within 30 days, are fever, chills, headache, fatigue, and muscle and joint aches. A classic circular “bullseye” rash is often seen at the site of the bite. Diagnosis is carried out by testing for the presence of Lyme antibodies, whereafter patients are typically treated with antibiotics.

From 1995 to 2015, the number of cases of Lyme disease in the U.S. more than doubled, reports the CDC. “We have a longer tick season with milder temperatures and warmer winters,” said Chuck Lubelczyk, Vector Ecologist at the Maine Medical Center Research Institute’s (MMCRI) Vector-Borne Disease Laboratory, also known as the “tick lab.”

Deer ticks thrive in moderate conditions. “They have a goldilocks complex,” Lubelczyk said. “They don’t like it too wet or too dry, too hot or too cold.” And they survive snow very well. It becomes an insulating layer for them, as does forest leaf litter.

The lifecycle of a deer tick is about two years. Animal blood is their only food, and they will feed on deer, rodents, dogs and humans. The mostly black, eight-legged tick will feed only three times in its life. When the minute larvae — no bigger than a dot — morphs into a nymph, it will take its first feeding. It will eat again when it morphs from the nymph stage to the sesame seed-sized adult. And finally, adults will feed to lay eggs. They can pick up the Borrelia bacteria on any of these feedings and may later transmit Lyme to their next host.

Over-hunting and deforestation had reduced the population of Borrelia-carrying white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in the U.S. to about 300,000 by 1930. But as hunting became better regulated and many former farms were abandoned, allowing the land to reforest, the deer population rebounded. It is now estimated to be about 30 million animals.

In some areas, a population explosion of white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) has also contributed to the spread of Lyme disease. Chipmunks and other rodents also host deer ticks.

Trail-running or hiking with your dog can expose your pet to deer ticks. “It’s one of the most common things we see as vets,” said Julie Bailey, Dean of the School for Animal Studies and Natural Science at Becker College in Massachusetts. “There’s been a very high incidence in tick-borne diseases and in dogs carrying ticks, and it’s gotten worse over the last five to ten years.”

In New England, as many as 50-75 percent of dogs will test positive for Lyme disease. Nearly 700,000 cases of Lyme in dogs have been reported over the past five years in the U.S. and Canada, according to IDEXX Laboratories, a pet healthcare company.

Bailey, who spent 15 years in clinical practice, recommends that dog owners check their pet thoroughly when they come indoors, paying particular attention to the feet and head. To prevent infection, there are now chewables and topical products in addition to flea and tick collars. There are also vaccines on the market for dogs, although Bailey says they are only about 80 percent effective. When asked how she protects her dogs, Bailey said she uses both the vaccine and topical preventatives.

Any dog that works or plays outdoors, whether it’s your backyard or on a farm, is at jeopardy of contracting tick-borne diseases. “If it’s a dog that doesn’t leave the house, it’s not high risk,” Bailey said.

Many dogs that test positive for Lyme will not show symptoms. If a person’s pooch develops a fever, seems lethargic, appears to experience joint pain or loses its appetite, it should be taken to the vet where the animal can be treated with antibiotics.

There is no cure for Lyme disease in dogs, said Bailey. A typical four-week course of antibiotics will control the disease, although it may reappear at a later date. “A small number of dogs can develop more severe, life-threatening symptoms,” Bailey warned. “Called Lyme nephritis, it can cause kidney failure.” Some specialists recommend urine tests for the life of a dog that has tested positive for the pathogen.

Much larger animals can also fall prey to tick-borne diseases. Moose (Alces alces) are plagued by winter ticks (Dermacentor albipictus), which can be found throughout most of North America. But they’ve hit the iconic North Woods grazer hardest in New England and the upper Midwest.

In New Hampshire, their numbers have dwindled from over 7,000 in the late 1990s to 3,800 today. Maine, which has the largest population of moose outside of Alaska, has experienced a decline from a peak of 76,000 to somewhere between 60,000 and 70,000. Minnesota has lost 60 percent of its moose in just 10 years.

These ticks are not the same as those that transmit pathogens to humans, and they generally don’t kill moose through infection. Instead, they at times suck the blood out of them altogether.

In some years, nearly three-quarters of moose calves fail to survive their first winter. “In the last three years, calf mortality in New Hampshire and Vermont has been over 70 percent,” said Peter Pekins, a wildlife ecologist at the University of New Hampshire (UNH). The numbers in Maine are similar.

Pekins told EnviroNews that they first began to suspect a problem in 2002, and began radio-collaring moose the following winter. That year they lost 50 percent of their calves. “Every other day I was getting calls, and there was another one found dead,” he said. “They were just loaded with ticks.”

One study in western Canada found an average of 33,000 ticks on each moose. But one moose in New Hampshire was found with 150,000 ticks on its body, and Pekins says they’ve counted over 90,000 on a single calf.

While adult moose generally survive these infestations, calves often can’t. “A calf could lose its entire blood volume in three weeks,” Pekins said. “When we find them, the calf is just skin and bones. They’ve been drained dry. Their tick loads are beyond belief and the whole body is just crusted with blood.”

Adult moose suffer in other ways. They’re attacked at the end of winter, when forage is at its poorest. They suffer blood loss, and to counteract that, the animal uses up its own fat and muscle for protein, Pekins explained. Tick-ravaged moose cows breed less too. “Back in the early 2000s, the proportion of yearling females breeding was over 30 percent,” the UNH scientist said. “The proportion of that today in New Hampshire is zero. They may have survived those ticks as a calf, but they are going to produce offspring at least one year later because they have to compensate for all that weight loss.”

The connection to global warming is undeniably clear. “Climate is really the number one threat,” said Collette Adkins, a biologist and attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, from Minnesota. “These shorter and warmer winters lead to better tick survival rates.”

In the Northeast, average annual temperatures have risen more than 2 degrees Fahrenheit since 1970, and winter temperatures are up about 4 degrees. Vermont’s winters have shortened by four days per decade over the past 40 years. It’s also raining more during New England’s winter season.

“We have seen winters become very short,” said Pekins. “This aids the survival of adult ticks in the spring and they have much longer to find hosts in the fall.”

The Center for Biological Diversity has petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to list the western moose (Alces alces andersoni) under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The western moose is a subspecies found in the U.S., from North Dakota to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and in Canada from British Columbia to western Ontario. In June 2016, the USFWS found that this species may warrant protection and launched a full status review.

“I have fond memories of seeing a mama moose and baby moose coming down to the water when I’d go camping with my family as a kid,” Adkins mused. “But my children have never seen a moose here.”

With both winter ticks and deer ticks benefiting from shorter, warmer winters, these pests’ days look bright. For moose, humans and their pets, it’s another story.

Lubelczyk warns, “We’re seeing the frontier for ticks move further east and north. We’re planning on seeing more Lyme disease.”

According to the CDC, about 30,000 cases of Lyme are reported each year. They note however, that this doesn’t represent every case of Lyme disease diagnosed in the U.S. The CDC conducted two separate studies, and this research found the number of people diagnosed with Lyme each year ranged from 288,000 to 329,000 — about ten times greater than the number of reported cases.

A 2015 study by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (Johns Hopkins) estimates the healthcare cost of Lyme disease to be as high as $1.3 billion a year in the U.S. Study author Emily Adrion, MSc, a PhD candidate in the Department of Health Policy and Management at Johns Hopkins, said in a statement, “Our data shows that many people who have been diagnosed with Lyme disease are in fact going back to the doctor complaining of persistent symptoms, getting multiple tests and being retreated.”

Lyme is not the only disease that deer ticks can transmit. “In addition to Lyme, we have at least four other pathogens that cycle in these ticks,” Lubelczyk explained. “These include anaplasma, babesia, relapsing fever and a viral disease called Powassan encephalitis.”

Sixteen cases of Powassan were reported in New York state between 2006 and 2015 — the highest of any state. In 2013, a 73-year-old Maine woman died of Powassan just two weeks after finding a tick embedded in her shoulder. About half the people who survive this illness are left with permanent neurological symptoms, according to the CDC.

Public health messages often focus on the tiny deer tick nymphs that are common in the summer months, but Lubelczyk advises, “People need to be aware that in the fall and early spring, adult deer ticks are out and they are a public health and veterinary concern.”

The connecting thread to the surge in tick-borne diseases is climate change. A report issued March 15, 2017, by the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health, puts it bluntly: “In communities across the nation, climate change is harming our health now.”

Writing in the report, Dr. Nitin Damle, President of the American College of Physicians (ACP), said, “My physician colleagues used to treat two or three cases a month during tick season; now each of us sees 40 to 50 new cases during each tick season.”

The report warns, “Anyone can be harmed by these diseases, but people who spend more time outdoors — where these insects and other disease-carriers live — are most vulnerable.” There is no human vaccine available for Lyme disease, although research is ongoing. For the approximately 10 to 20 percent of patients who develop Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS), a debilitating disease that includes extreme fatigue, pain, arthritis and cognitive issues, several new treatments show promise. These include antibiotic cocktails, new drugs and dosing regimens, and research into how the patient’s gut bacteria could aid in alleviating symptoms.

Lubelczyk said they are working on a pilot study to see if it would be possible to create a tick forecast. That might assist the public and health community in preparing from year to year, as factors such as cold temperatures, snow cover and precipitation vary. Drought reduces tick numbers, as does a longer, colder winter season — as Thoreau would have experienced in his lifetime.

But the long-term trend is clear. According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, “By the end of the century, the typical summer in upstate New York may feel like present-day summer in North Carolina.” By then, one is left to wonder if the iconic moose will have vanished from the North Woods entirely. Nevertheless, people will still be here, along with their pets. And the ever-proliferating, disease-carrying ticks that can infect them will still be lurking in the woods.

ADDITIONAL VIDEO RESOURCES:

FILM AND ARTICLE CREDITS

- Dan Zukowski - Journalist, Author

![Leading the Charge for America’s Wild Horses on Capitol Hill: NBA/NFL Celeb. Bonnie-Jill Laflin: ‘[Politics] won’t stop us from fighting’](https://cf-images.us-east-1.prod.boltdns.net/v1/static/1927032138001/f46b2158-cead-47f0-ab44-4b027059411a/4e4afcf2-937d-4a9d-acba-1b82e2efd4c6/160x90/match/image.jpg)